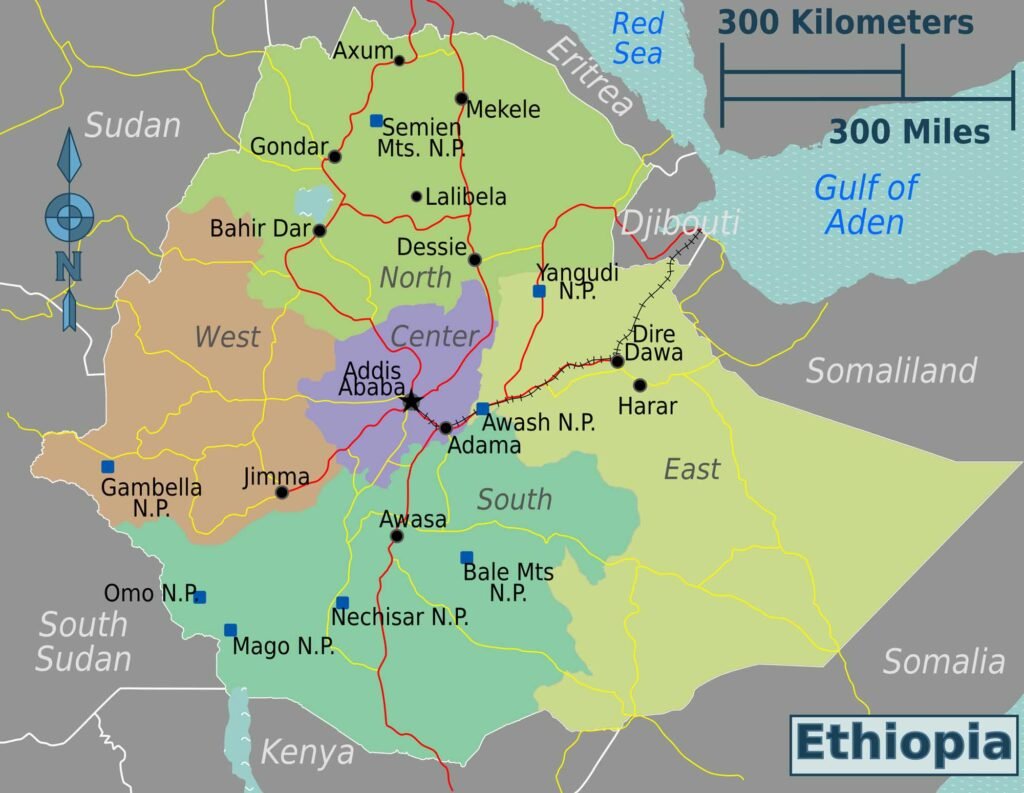

Ethiopia is the most populated landlocked country on earth. For a population of over 120 million people, that is a huge problem. The issue of Ethiopia’s port access, or rather the absence thereof, is emerging as a potential source of conflict in East Africa.

In a recent state-televised documentary aired on October 13, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed revealed a geographical conundrum that has been plaguing the landlocked country for an extended time – the critical need for a strategic sea port. He claimed that the Red Sea should be seen as Ethiopia’s natural boundary, and that securing a port on this sea was key to breaking free from a “geographical prison.”

This assertion has triggered serious diplomatic concerns, not only because of the ominous implications of these words for Red Sea neighbors – Eritrea, Djibouti, and Somalia – but also because of the increasingly belligerent attitude that Ethiopia is showing.

“An Ethiopian official told The Economist, ‘If port access is not achieved by other means, war is on the way.’”

This is part of a larger issue that has been haunting the Ethiopian government over the years. Let’s unpack the importance of sea port access for Ethiopia and whether PM Abiy Ahmed, ironically the Nobel Peace Prize winner of 2019, could potentially instigate another conflict with neighboring countries.

Ethiopia’s Historical Struggle for Port Access

The issue of insufficient port access is not a new idea for the Ethiopian political landscape. Their concerns have significantly increased since Eritrea gained independence in 1993 and relations soured over a border dispute in 1998.

In the pre-independence era, being a federalized part of Ethiopia, Eritrea’s Red Sea ports provided crucial access for Ethiopian external trade. The Assab port in southeastern Eritrea accounted for approximately 70% of Ethiopia’s external trade.

However, with Eritrea’s declaration of independence, Ethiopia became landlocked and was heavily reliant on Eritrea for port access to cater to its trade needs. But the outbreak of war over the disputed Badme region in 1998 ruined relations and Eritrea withdrew port access from Ethiopia.

Ethiopia resorted to signing a deal with Djibouti to use the latter’s port, which now handles over 90% of its trade. This dependency costs Ethiopia about $1.5 billion a year in port fees. Plus, it also creates strategic vulnerabilities as both the port of Djibouti and the A1 highway connecting it are crucial lifelines.

The geopolitical significance of this issue came to the forefront during the Tigray War. The Ethiopian government feared Tigrayan rebels reaching and blockading the A1 highway, knowing the severe damage such a blockade could inflict on Ethiopia’s economy and governance.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s Current Diplomatic Endeavors

To limit Ethiopia’s over-dependence on Djibouti, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has been actively trying to negotiate access to other Red Sea ports. His government started constructing a transport corridor to Kenya’s Lamu port, and part of the peace deal signed with Eritrea in 2018 was aimed at restoring access to the Assab and Massawa ports.

However, progress has been slow and often contentious. Recent fallout between PM Abiy and Eritrea’s long-standing leader, Isaias Afwerki, has jeopardized Ethiopia’s access to Eritrea’s Assab and Massawa ports. This falling out is deeply intertwined with Ethiopia’s internal politics, especially the conflict with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).

The Future at Stake

While a full-blown war feels unlikely and undesirable, the increasingly confrontational stance of Abiy Ahmed cannot be ignored. PM Abiy’s zealous approach towards securing Ethiopia’s geostrategic interests was reflected in the construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, further antagonizing Sudan and Egypt by potentially limiting their downstream water access.

PM Abiy’s unpredictability combined with his unveiled assertion about ‘a future conflict’ makes us skeptical. Considering its strategic significance for Ethiopia, securing port access could well become another regional flashpoint in the future. A renewed conflict would only bring further instability to the already volatile Horn of Africa region.

In conclusion, Ethiopia’s port access dilemma has the potential to fuel regional tensions, hamper trade flow, and trigger an undesirable conflict. And as Ethiopia’s leader digs in his heels, eyes are focused on possible diplomatic solutions that will avert another crisis in a region already fraught with tension and instability.

Leave a Reply